RuBisCo-The Global Paradox

Why Earth’s Most Important Protein is Our Biggest Climate Vulnerability

MCC

12/1/20252 min read

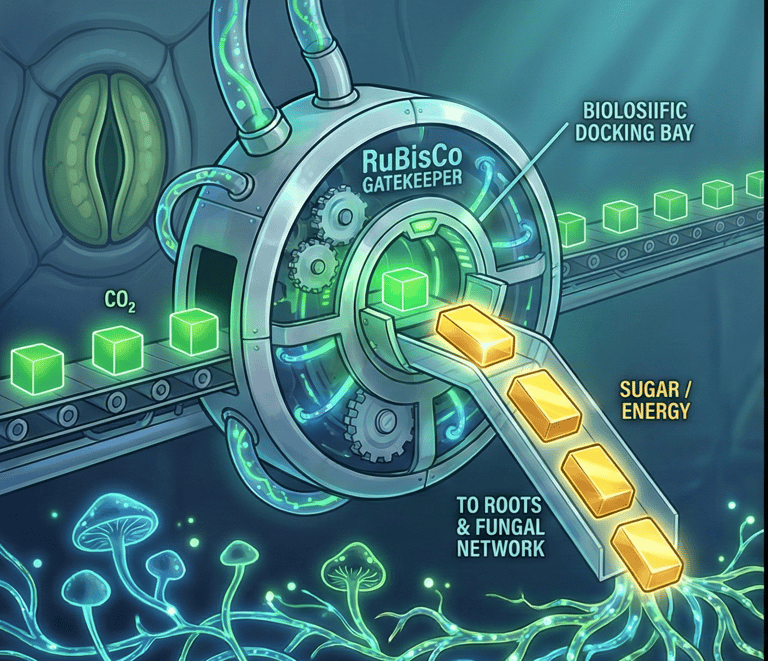

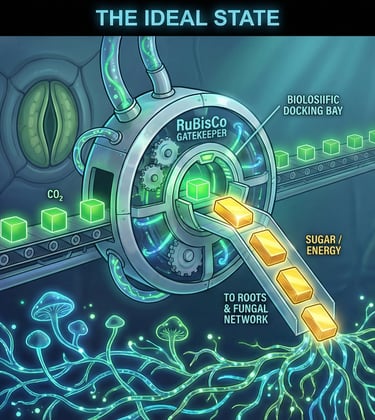

In the vast machinery of life, no single molecule is more critical than RuBisCo (Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase). This enzyme is the silent engine of photosynthesis, the chemical conduit that captures atmospheric carbon dioxide CO2 and converts it into the organic sugars that build every leaf, root, and forest on Earth. RuBisCo is arguably the most abundant protein on the planet, serving as the universal Carbon Gatekeeper.

The Flaw in the Foundation

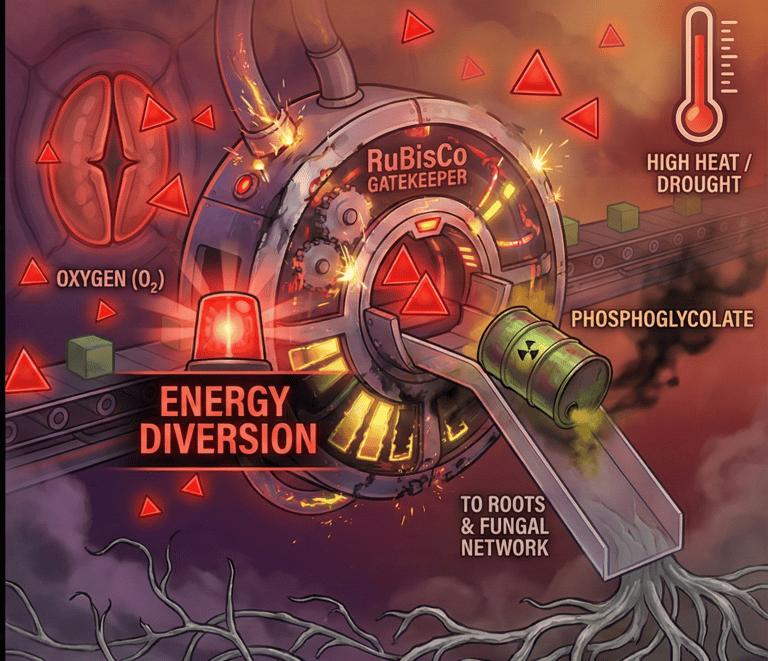

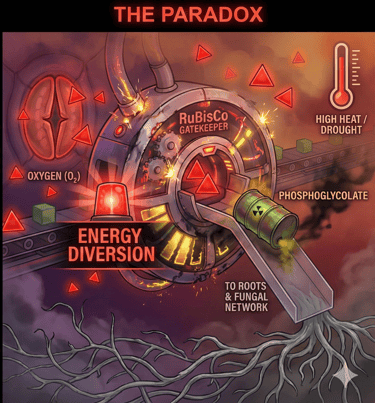

The core function of RuBisCo is simple: carboxylation—binding a CO2 molecule to a sugar in the leaves' chloroplasts to start the process of sugar production. However, this critical gatekeeper has a fundamental, ancient flaw that creates a global vulnerability.

RuBisCo evolved millions of years ago when Earth's atmosphere was low in oxygen O2. As O2 levels rose, the enzyme didn't adapt quickly enough, leading to a molecular identity crisis.

It frequently mistakes O2 for CO2, initiating a wasteful process called photorespiration that consumes energy and releases captured carbon. To compensate for this inherent inefficiency and clumsiness, plants must dedicate massive amounts of their own energy to producing huge quantities of the enzyme, severely limiting the total potential of the terrestrial carbon sink.

The Cascading Stress Effect

This intrinsic flaw is accelerated dramatically by climate change, creating a phenomenon we call the Cascading Stress Effect.

When plants are hit by above-ground stressors like heat and drought, they deploy a crucial defense: closing their stomata (pores) to conserve water. This action starves the leaves of CO2, exacerbating RuBisCo's flaw and collapsing the plant's net sugar production.

The plant, facing low Gross Revenue, must divert its limited resources to its own survival (like growing deeper roots).

This creates a critical downstream financial crisis: the Influence on the Mycelial Network. The mycelial network relies on the plant's Net Profit (sugar available for trade) to fuel its own nutrient-scavenging and immune functions. When the net profit collapses due to RuBisCo's poor performance under stress, the fungal network is starved, threatening its ability to sustain the ecosystem's resilience.

The Breakthrough: Biological Redundancy

The solution to this global paradox lies not in human engineering, but in nature's most resilient strategies. We found a perfect example in the ocean's Oxygen Minimum Zones (OMZs). Stanford scientists discovered microbes (cyanobacteria) that thrive in these harsh, low-oxygen waters by employing two different forms of RuBisCo simultaneously.

Form I RuBisCo: The standard engine, often protected by a specialized structure called a Carboxysome to concentrate CO2.

Form II RuBisCo: A specialist optimized to efficiently fix carbon even when O2 is scarce, like in the deep soil or OMZs.

This dual-enzyme strategy is the ultimate example of Metabolic Flexibility—a biological insurance policy that guarantees performance when the environment shifts.

The Mycelial Mandate

This oceanic breakthrough provides the core scientific foundation for our Metabolic Flexibility Potential (MFP) protocol. We must move beyond simply planting trees and reward the biological systems—the plant-fungal partnerships—that exhibit this same genetic redundancy and strategic defense below ground. By incentivizing the terrestrial system to overcome RuBisCo's innate flaw and stabilize the energy flow to the mycelial network, we can protect the planet's most critical carbon-sequestering machinery from the Cascading Stress Effect and unlock the true, immense potential of the terrestrial carbon sink.